Do I need to build a second home?

Vacation homes are a substantial portion of our portfolio, and we consider them an essential part of a balanced and healthy life in the big city.

Manhattan rarely offers anything else than just tiny apartments with minimally-acceptable floorspace, even for high-income dwellers. Close to what the Germans call existenzminimum, the bare minimum to exist, to be. We tolerate being crammed into small spaces in the city because we can get out, find a place where to relax, breath some clean air, have a connection with nature, and feel the weather. Life in the big city fosters the psychological and physical need to escape from it and reconnect with nature on a regular basis.

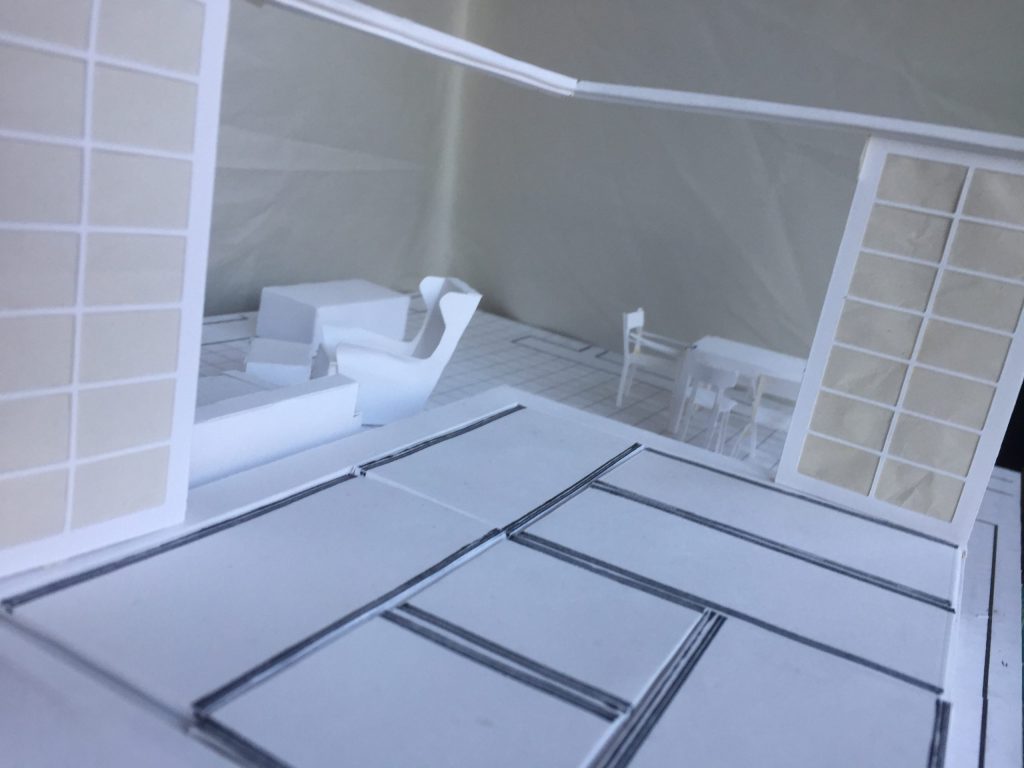

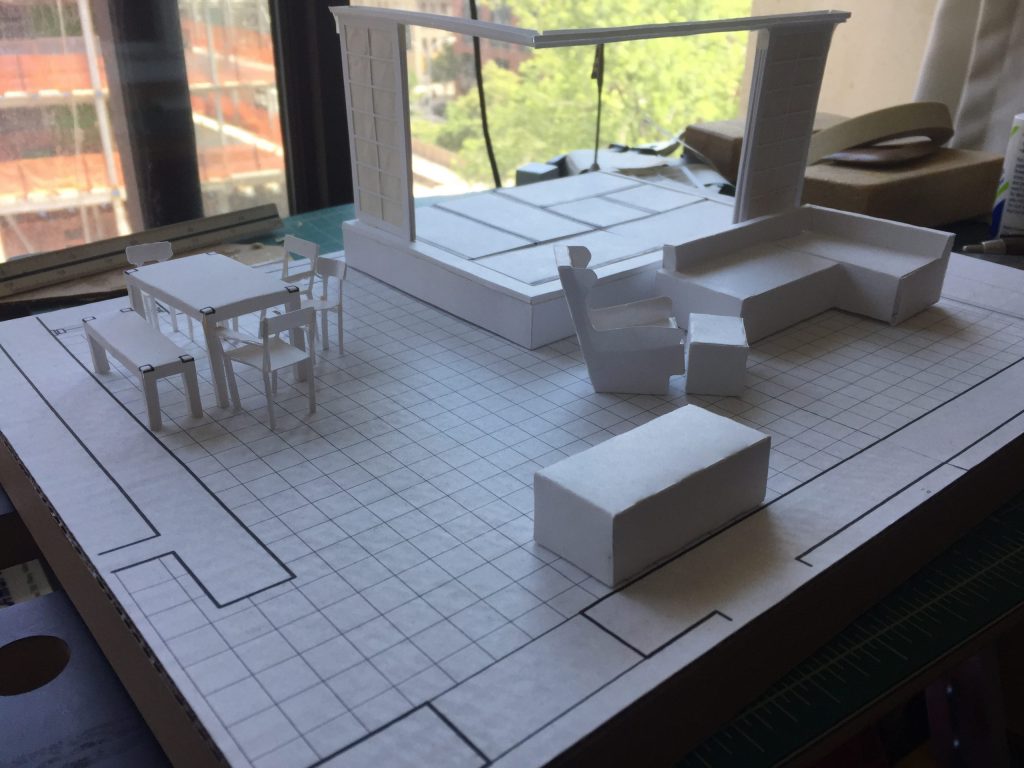

In that direction, the construction of a holiday home is the best opportunity to build your own space; a space that will become the center of your world.

Semiotician Fernando Andatch* explains our meaningful relation with the built environment when building a holiday home:

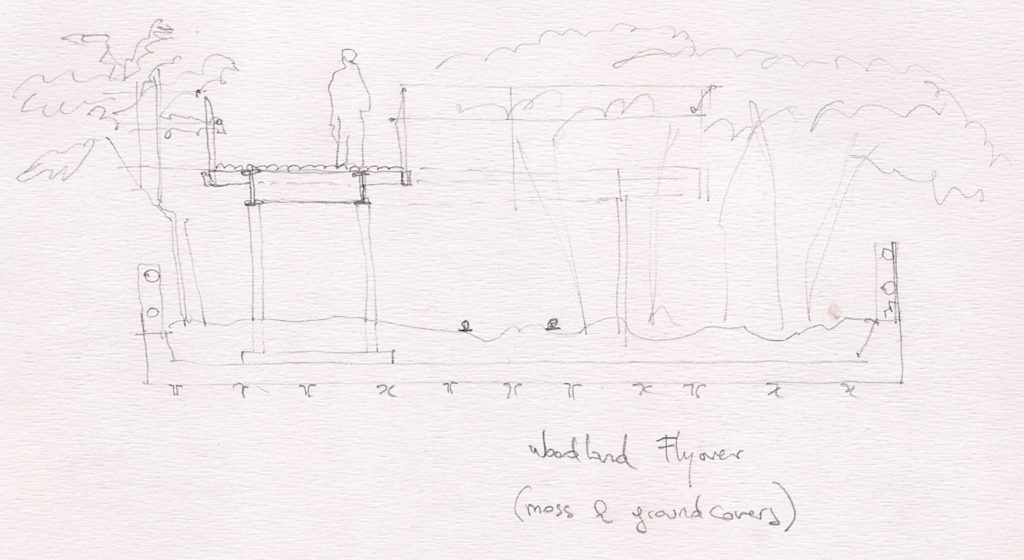

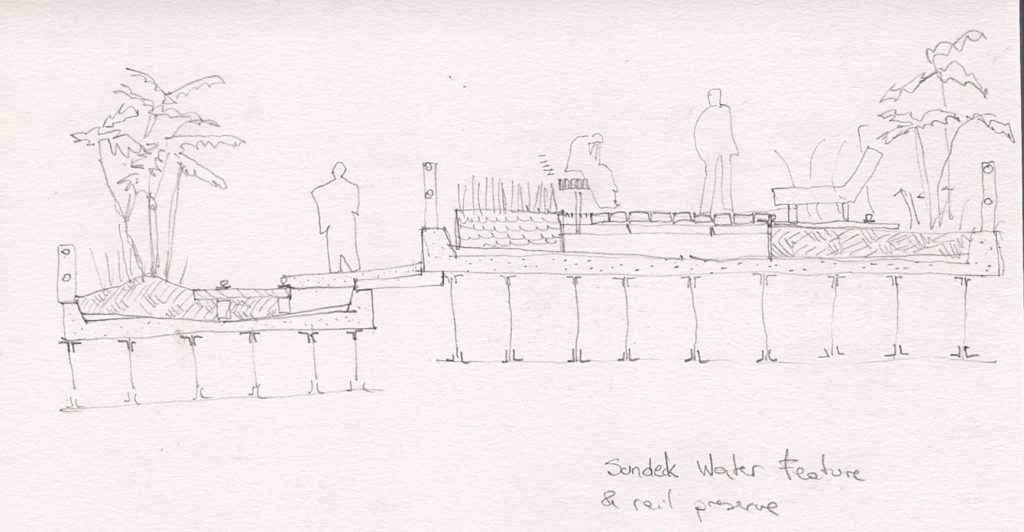

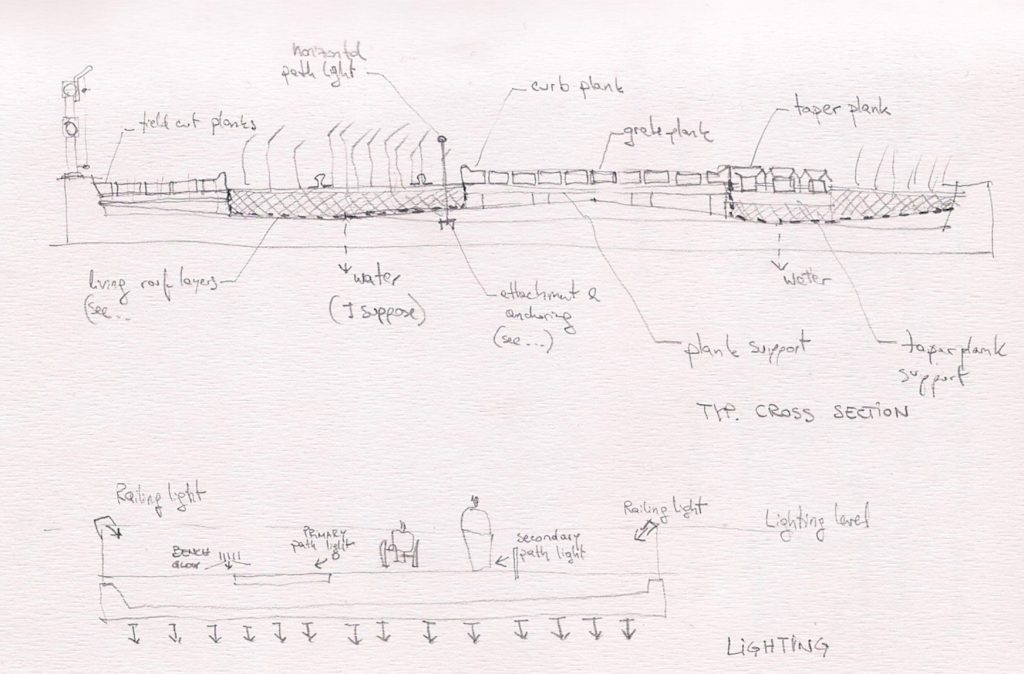

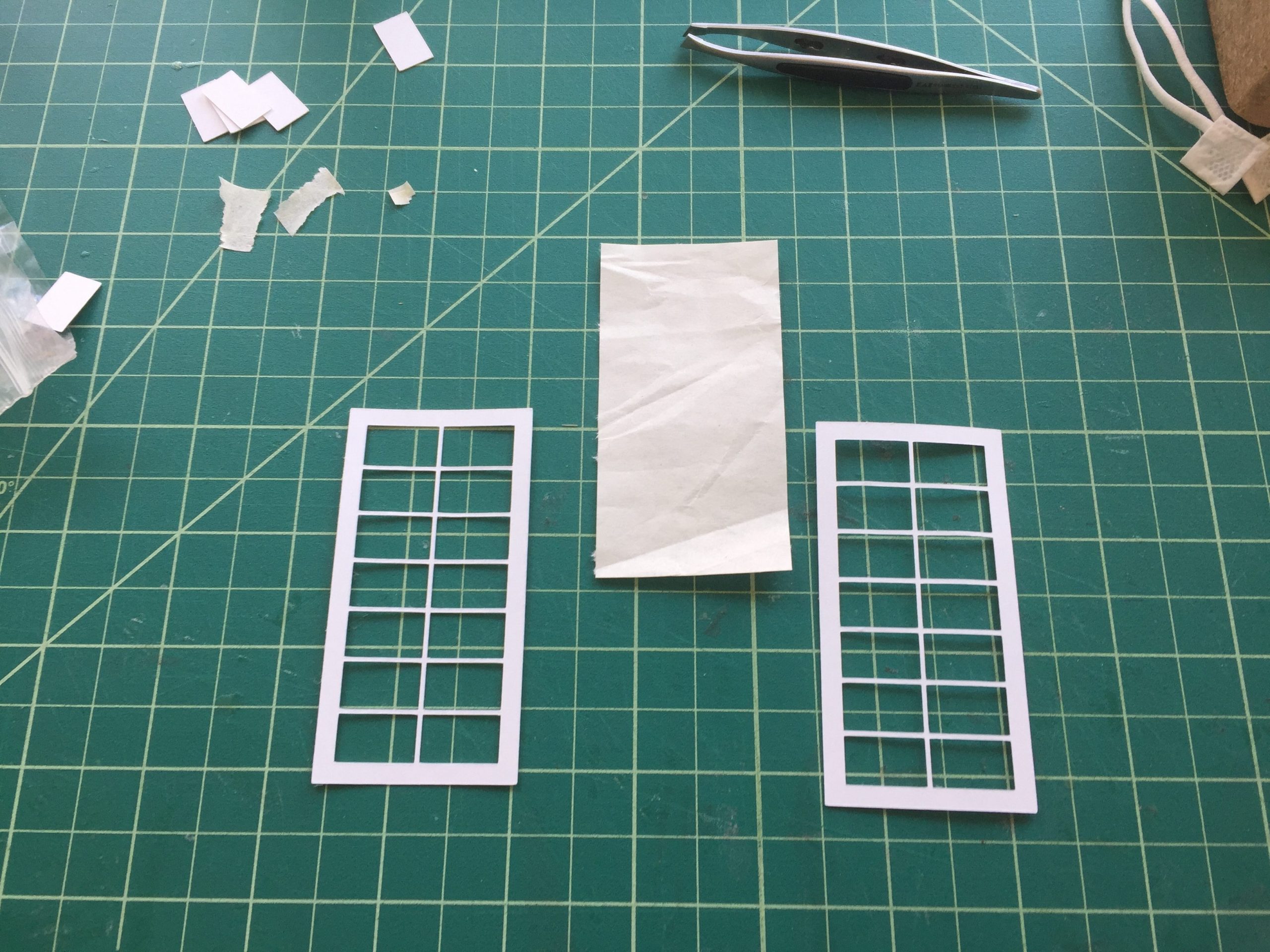

Successful houses demonstrate a careful consideration to their natural surroundings. It is not necessary to “retouch” trees or ponds to make them become components of an architectural code where the meaning is clearly defined: The piece of landscape that we frame with a window belongs to the system of symbols and signs of our built environment with the same rights of the bricks or the wood timber used to build it.

To make a project, architect and client use signs, elements to satisfy physical needs (to stay away from the weather and intruders), but it cannot be done without aspirations or desires. These aspirations are codified by the community: we need to feel comfortable, important, modern, etc.

Thus, the act of building is a dialogue between ecology and mythology. A dialogue between what is already there and what we want to see and do there.

What about buying an existing house and then renovating it?

A renovation is also an excellent option, and considering sustainable goals, it is always better to reuse and adapt existing buildings than using new land for a new development. You can see one example of renovation here.

However, we must consider that existing houses were originally built for different people, with different hopes and desires. They showcase a different set of connections with nature that are not your own. And most likely, they have a standard spatial distribution, which is not tailored to your needs. They may have the amount of rooms you required, but the plan layout and the relation of these rooms with the exterior would be following someone else’s intentions.

Therefore, renovations have to be substantial, deep, and sometimes even radical to really transform the essence of an existing house.

Fundamentally, we all experience our vacation time differently, and we exercise a natural tendency towards the customization of our environment.

In this direction, Andatch also explains how holiday homes belong to a different “time zone”:

The holiday home is a transgression of myths. Transgression, understood etymologically as “act of crossing, passing over”, related in a way to switching teams. From the team of the workers, to the team of the holidays makers. This is an abrupt personality change.

The holiday home is a house where we stay a bit [of time] and live a lot [of time]. This apparent contradiction is resolved when we analyze the time dimension in two categories with emotional charge. One of this categories reads time as memorable and enjoyable, while the other represents just waiting and forgetting.

In the holiday house we stay just a fraction of the whole year, of the time that we consider normal time. We can call this normal time chronic, from the Greek Kronos, a time that we can measure and calculate. It is composed by a continuum of small fragments, identical between each other according to a social convention. Is the time of work, routines, and duties. It is the essential primary commodity of bureaucracy, and the bureaucratization of private life.

About a sixth of this time is the time we spend in a holiday home. This is the first scandal of practical reason. However, we live there much more of the other time, the time of the opportunity that we cannot let go. These are the times that we designate with the Greek name Kairos (Greek for occasion, opportunity). The strength of this time is in its condition to of been memorable, establishing a cut with normality. In this time we have weddings, honeymoon, trips, and of course holidays in this second house. This time is not composed by similar pieces that are all the same and that we can repeat of Infinitum but it’s characterized by a maximum of expectation, high tension, and passion in space.

Usually we say “let’s go out”. And it is not just leaving the apartment or the city. We are talking about abandoning Kronos to get into the exceptionality of Kairos. Here is the transgression that we were talking about: we switched teams and to stopped being a citizen adapted to the norms of the polis where he leaves, works, and dreams. Thus we change habits and clothing from every day life, and we access another space with another time.

The permanent dwelling home is located in the antipode of the natural, because it is the definition of urbanity, of the civilized effort to control chaos. Considering that, the holiday home is located in a place in-between. It is neither totally urban, nor totally savage. It limits a space of new possibilities, of new meetings with respect to the everyday. This is the construction of the myth of the return to the origins that Rousseau was talking about: The natural man (man of the nature) that has to replace the social man, the man of the man.

What about moving to the suburbs?

It is worth mentioning that a holiday home is not —and cannot be— a suburban house. The suburban house still belongs to the space-time of the city. It is a house used in the everyday, and our rhythms and times are the times of work, routine, and school. Telework fueled by the pandemic was pushing our Kronos time in different, new directions, but still, it was not morphing it into Kairos.

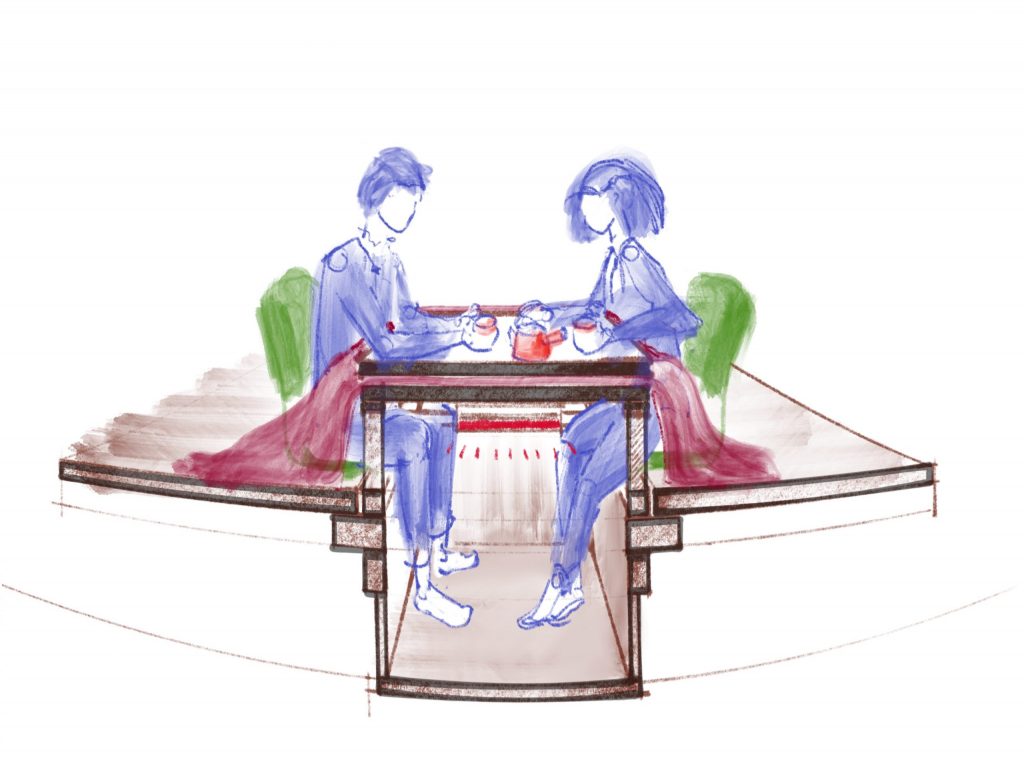

In the holiday home we are different and we leave the life: we dress comfortably, we eat, drink, and relax. Because of that, the kitchen is one of the essential spaces of this house. Usually, there are two kitchens, one inside and another outside.

Andatch explains how we change during the holidays:

A picture of a half naked model seduces us, because it is some kind of in-between, not totally urban, not totally explicit. The model seduces because it swings as a pendulum between two worlds. Between what is free, spontaneous, care-free, and what is built, fixed, normalized. The holiday home creates a space with a singular wish, the wish of being someone else, at least in its own land. It is also the abolition of the sedentary conduct, albeit temporary, we value the environment in which everyday life is forgotten, with the necessary anesthesia.

In the holiday home everything changes, beginning by its inhabitants. Clothings, gestures, and schedules have to be readjusted to transgress normality without falling, however, into anomie.

The house for holidays is the art of time outside time and a place outside place, that wishes to escape the dichotomy that limits the day Sunday works of the contemporary man.

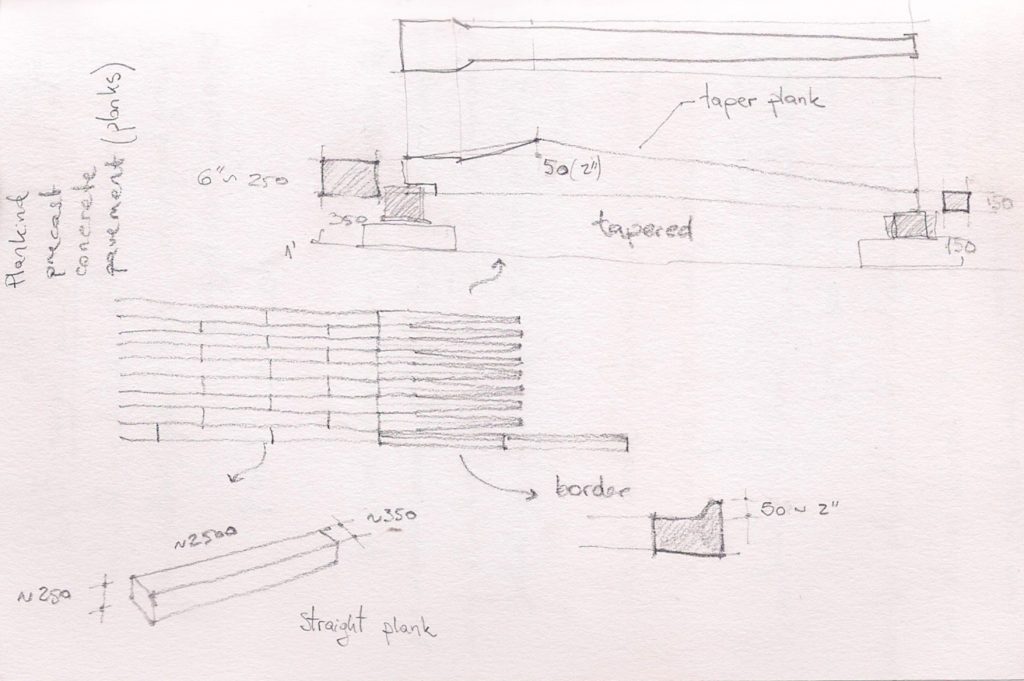

Thatched roofs, bricks or stucco, are chosen as materials that have been semiotics-iced. And they are located in classes that exclude the from within an architectonic system of materials that belong to the city.

*Andacht, Fernando: Entre signos de ‘asombro’. Antimanual para iniciarse a la semiotica, Trilce, Montevideo, 1993 (The translation is mine)